A TALE ABOUT LIFE INCLUSION

DEH - europeanhouse.org

Labour and emigration in Kyrgyzstan

Every year the labour market in Kyrgyzstan has to absorb large numbers of education graduates. The relevant age

group of 15–29 year-olds makes up 31% of the entire Kyrgyz population, a much greater proportion than in western

European societies. Large youth cohorts require a dynamic economy in order to find employment. At the same time, young people are a precious asset for a country, holding the key to future growth and prosperity.

The overall unemployment rate that emerged from the sample is high at 20%. Young men are more likely to be

unemployed than young women and job opportunities are particularly lacking in rural areas, where unpaid household work frequently takes the place of salaried employment. Education plays an important role in determining early labour market outcomes. Those with only basic education are most likely to be engaged in unpaid household work, and if they do enter the labour market, they predominantly work in the informal sector. This is also true for those with initial vocational education and training (VET) and for those with general secondary education: both these groups of graduates mainly work in unregistered jobs and without contracts.

The labour market is strongly segmented into a formal and an informal sector. For their first job graduates are more likely to enter the informal sector than the formal sector. Apart from occasional examples of high wages, the overall quality of employment in the informal sector is much lower than the formal sector. The working week is almost 10 hours longer and job instability is high, with almost two-thirds of informal sector workers losing or leaving their informal job over the course of the observation period. In contrast, about three-quarters of job holders in the formal sector experienced job stability over the entire observation period. With little movement between the formal and informal sectors, the composition of the Kyrgyz labour market appears to be largely fixed and generally does not allow for upward mobility from the informal to the formal sector.

Personal networks are of overwhelming importance in the search for work. In contrast, employment agencies and

job advertisements play only a negligible role in matching job seekers to vacancies. This is true irrespective of the

educational background of job seekers and the type of job sought. This highlights the weak institutional support for

moderating the transition from school to work in Kyrgyzstan.

A high proportion of young people enter the labour market without having completed education. The rate of dropouts is 14% across all education levels, with virtually no difference between men and women. Particularly high dropout levels can be observed in higher education, in initial VET and in basic general education. The high dropout rate in basic general education gives most cause for concern as dropping out of education at this level seriously decreases life course opportunities and is not easily compensated for later in life.

Source: ETF

When a country has a mismatch between what its labour market needs and the education and skills of its young people - what's the answer? Kyrgyzstan is working hard to address this imbalance by training young women and men in job skills that are actually in demand in its transformed economy.

In Kyrgyzstan entering the labour market is highly dependent on private resources, particularly in terms of exploiting social connections to find employment and having sufficient private financial resources to attend education. This situation causes inequalities and inefficiencies in the transition from school to work. In order to increase the geographical and vocational distance that talent, skills and qualifications can travel, labour market and job placement services should be improved, career guidance strengthened and the quality and labour market relevance of education developed and enhanced.

Within the VET system, efforts should focus on expanding work-based training, upgrading theoretical training components and updating teaching content. In the light of the highly fluctuating informal segment of the labour market, which absorbs most graduates of initial VET, there should also be more emphasis on delivering

essential entrepreneurial skills in order to strengthen the overall entrepreneurial dynamic among young people and

promote the growth potential of businesses.

The Kyrgyz private sector is largely dominated by unstable and precarious informal employment.

The general lack of employment opportunities in rural areas severely limits the options for school graduates. It leads many young Kyrgyz to work without a salary within the family, or to migrate – either abroad or to the comparatively dynamic labour markets of Bishkek and other urban centres, contributing to high unemployment and overburdened infrastructure in these areas. In order to improve local prospects for school graduates in rural areas, it is necessary to focus on rural development that expands agricultural productivity beyond the subsistence level. Rural vocational schools can play an important role here by providing skills training for entrepreneurial activity and self-employment. They can also offer courses in productive agricultural activities, and act as a focal point for local experimentation and knowledge dissemination in developing sustainable and cost-effective agricultural activities.

Copyright © All Rights Reserved

DEH

Uraniavej 5

1878 Frederiksberg C

Every year, tens of thousands leave the republics of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan — the poorest countries in Central Asia — to find seasonal employment in Russia’s main cities. Many stay for years; others never return home, but their remittances form an important share of their country’s economy. The World Bank estimates that, in 2014, money sent back home by migrants was comparable to 36.6 percent of Tajikistan’s GDP, and 30 percent of Kyrgyzstan’s.

Moscow’s Little Kyrgyzstan presents the story of ten immigrants from Kyrgyzstan living in Moscow, showing the diverse reality of millions of immigrant workers in Russia in their own words

The transition from school to work represents a critical stage in young people’s lives. It is usually understood as

the period between leaving the education system and entering the world of work. School leavers have to find

employment which suits their interests and education to provide fertile ground for future professional development.

Education is the main resource that young people have when they enter the labour market. Unlike older, experienced workers, young graduates do not have a work record or employment history to prove their employability. The opportunities available to them on entering the labour market are also closely related to the demographic structure and the economic situation in which they find themselves, namely the size of the youth cohort entering the labour market in relation to the demand for new workforce. The larger youth cohorts are that enter the labour market the more vibrant an economy needs to be in order to absorb them. When there is an economic downturn, often the ‘last in first out’ rule applies, and young people are the first ones to be laid off. It is also generally more difficult to find a job during an economic depression, when overall labour turnover decreases considerably.

Young people’s opportunities of finding work vary significantly from country to country. One reason for this is the

difference in the mechanisms involved in entering the labour market, leading to different opportunities being available in different countries for young people with similar personal qualities, education and skills. Thus, early career chances are shaped considerably by national institutions, especially by the characteristics of countries’ education systems and by the organisation of the labour market.

Source: ETF

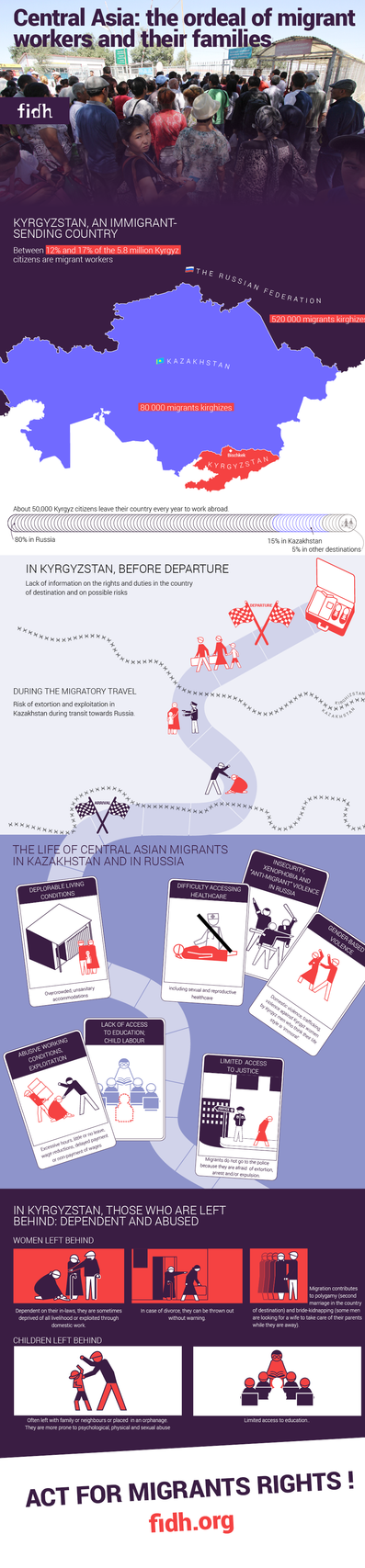

In Kazakhstan and in Russia, the rights of migrant workers from Central Asia are regularly violated.

The discrimination experienced by women and children who are affected by migration, whether they leave or stay behind when their partners/parents migrate. Those who emigrate have to live in crowded and dirty lodging, and have only limited access to health services (including sexual and reproductive health) and education. Women are especially vulnerable to abusive work conditions.

Many of those from Central Asia are also targets of racist and xenophobic actions left totally unpunished, particularly in Russia: "I work from 10 in the morning until 10 at night. My husband comes to get me every night because I am afraid to go home alone. It is very dangerous for the Kyrgyz. Once, in the subway I saw three Russians beat a Kyrgyz, shouting ‘you’re a Muslim’. No one said anything", said sadly Anora from the province of Chuy (north Kyrgyzstan). The report also denounces the social phenomenon of the so-called “Patriots” in Russia, where Kyrgyz men carry out assaults on Kyrgyz women because they think their life style is too loose, and even ‘immoral’.

1. Which countries are Kyrgyz migrant workers mainly going to?

2. What are the problems migrant workers regularly meet?

3. If you compare to Denmark - what are the differences and the similarities with Kyrgyzstan?

4.

Besøg undervisningspakken: